On Preservation

October 2013

Abstract:

It takes ten days before the eggs of the silkworm hatch. The caterpillar will then eat mulberry leaves, day and night, and wrap itself in a cocoon of silk.

The dirt was swept up by the wind into the city streets. In the morning, an old man with a crooked back, walking slowly, picked up the bits of paper and plastic from the front yard of the Silk Museum. This is what he did, year in, year out, every single day. I greeted him daily as I made my way to the museum. He never replied, but I thought, ‘that gardener, he’s a nice man’, and I kept greeting him. In his front yard grew plants, in the flower beds flowers bloomed, shrubs and trees were neatly trimmed, and the path was well-looked after.

In the Silk Museum of Tbilisi, time seemed to have stood still. Visitors would find themselves amidst something that seemed entirely untouched. Something that was resting and could not wake up. It felt like a time capsule, on a journey through space.

The museum houses a large collection. Cocoons sorted in filing cabinets, in all the different shades of white, yellow and grey. Rows upon rows of pinned moths, display cases, cabinets. Carefully selected leaves from certain trees in a frame. People walked through the halls and saw fibres hundreds of meters long and as thick as a needle. Here, things were in a different dimension, shrouded in a deathly hush.

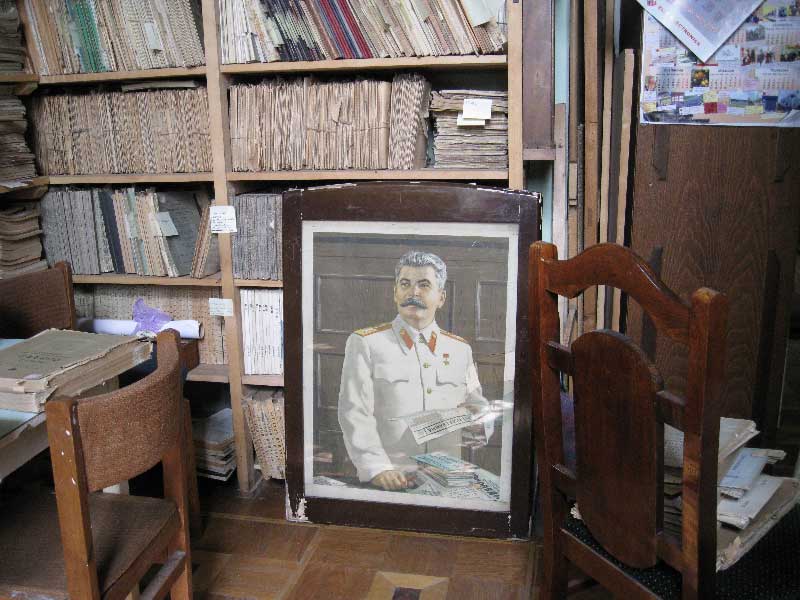

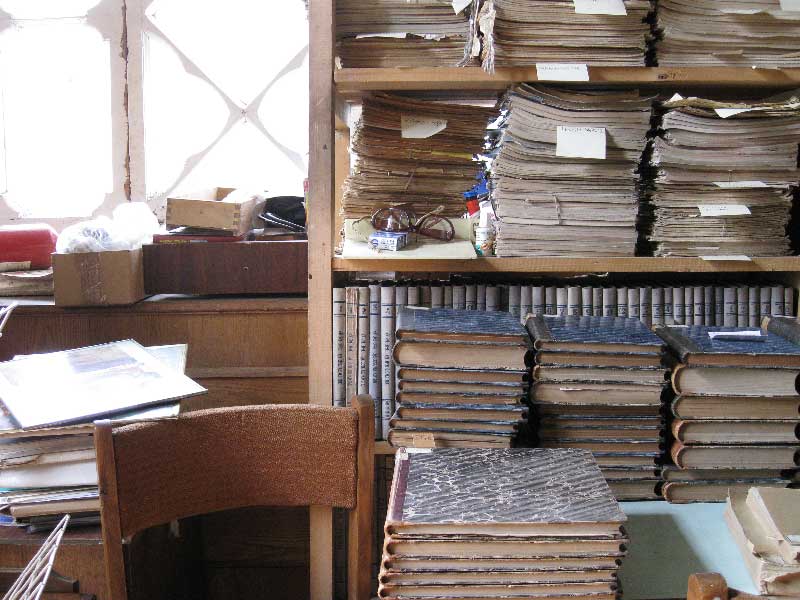

The archives of the museum consisted of high stacks of paper, loose sheets scattered on tables. It was impossible to sort through. Hundreds of books bound in leather, containing absolutely stunning drawings. One of the studies had a portrait of Stalin on a wall, with a silky smooth skin, but his eyes were impenetrable. He was looking at something behind me, shapes in a bottle of formalin. Unmoving small creatures. Perhaps they had been staring at each other for decades, completely misunderstanding each other.

A long time ago, the items would have been dusted time and time again, with a soft cloth. But, as the museum was forgotten and a realm crumbled outside, nothing shifted within the walls of the museum for decades, not one cabinet. The dust in the museum halls had settled.

During my visit to the Silk Museum, something began to dawn on me. Slowly, I started to understand more about the preservation of a collection. I saw the result of inaction. Why had this collection of the Silk Museum in Tbilisi, which was of course exceptional and by now one of a kind, been preserved? This in contrast to other similar collections that certainly would have been equally special, such as the famous nineteenth century silk collection of the textile laboratory in Lyon.

Collections fall apart when a new and attractive display is made. When an exhibition is put together, with the aim to make wonderful objects more accessible and visible for a large audience, existing collections are often literally cut to pieces, with filing cabinets emptied and everything sorted anew.

But when collections are merged, something is lost. Things that were once carefully positioned next to each other are separated. A logical system that was previously created is lost, and with it a finely aged relationship. Romance destroyed by modernization.

The collection of the Silk Museum in Tbilisi was preserved precisely because it had remained invisible to the public, like a treasure. This was quite odd. Tbilisi was on a ‘silk road’. Although there was no longer any production or significant processing of silk in the region, the history of the silk trade has been very important for the character of this place. Because of the trade route, Tbilisi has a unique blend of Oriental, Western and Arab cultures. But the silk collection rarely received a visitor.

When someone did visit, it was usually for a different reason. Someone would come to inspect the building, to see if the building could be used for a different purpose. Lavrenti Beria also visited the silk collection, in 1933, at the opening of the adjacent stadium named after him. He was captivated by this time capsule and decided that it should be preserved. And for fifty years, nothing happened, until the management of the building was transferred to the stadium in 1986, which had been renamed to ‘Dynamo’. A plan was made to turn the building into a hotel. The carpenter who was hired to remove the cabinets of the collection determined that it was impossible to reconstruct the beautiful furniture after disassembly, and he refused the job. The furniture is a unique example of 19th century craftsmanship. The Dynamo stadium decided to postpone the job, and one of these days became none of these days. The building was left completely unattended. The roof began to leak. During the civil war in the nineties of the previous century, the collection was rescued by a group of enthusiasts. The building received some makeshift repairs and was once again opened to the public. It is only since 2006 that it became a registered museum, and it is now under the protection of the ministry of Sport and Culture of Georgia. However, it does not receive many visitors, and the collection remains a hidden gem.

Because of the lack of interest from the outside world, luck, and the unconditional faith of a single attendant, this collection was preserved. A ‘Wunderkammer’ should not be entered too often!

Translated by:

Published:

This article appeared in October 2013, in the publication at the ‘Wunderkammer’ exhibition of the Katharinenhof Museum (Kranenburg, Germany).